Billy Oatman, the First Black Player to Win Rookie of the Year, Dies at 57

Billy Oatman, a former PBA Exempt Tour player who started his professional career at age 40, passed away earlier this week due to complications of a stroke. He was 57.

Oatman is survived by his daughter, Taylor Imani Haynes, and his father, William H Oatman III.

The Chicago native won the Harry Golden PBA Rookie of the Year award in 2006-07, becoming the first Black player to win the award. At 41, Oatman was also the oldest recipient of the award.

Though he never captured a PBA Tour title, Oatman’s impact on bowling transcended far beyond his résumé.

“Billy was one of those guys, he was just infectious, man,” said George Wooten, a bowling writer of more than 25 years. “He’s got that 1000-watt smile. He enjoyed being a professional, shaking hands and signing autographs. He enjoyed everything about it.”

Leroy Johnson, a fellow Chicago bowler nine years Oatman’s senior, said he first met Oatman when Oatman was 15 or 16.

“His mother was bringing him around and talking as if he was going to be the next biggest thing,” Johnson said. “We had our doubts, but we soon learned.”

Oatman bowled collegiately at Vincennes and Wichita State, but decided not to make the leap to the PBA Tour. In 2006, Oatman was bowling amateur events around the country when he met his wife Annette, she said.

Annette said she asked Oatman, 40 at the time, why he hadn’t gone on Tour.

“Do you want to spend your life saying I woulda-coulda-shoulda or do you want to go out and see if you can make it?” she asked him.

Around this time, the PBA had adopted an Exempt Tour format. Players who could earn a spot on the exempt players list would be guaranteed entry into each event that season.

“When that Exempt Tour came around, he was like, ‘This is my last chance to live my dream and to really do it at the level that I know I can do it,’” Wooten said.

Oatman competed in the Denny's PBA Tour Trials that June, needing a top-10 finish to earn an exemption. He finished 11th, 34 pins behind 10th-place Del Ballard Jr.

Oatman was so distraught and frustrated that he went outside to decompress, Wooten said. As he lugged his equipment to his van, his fortune began to turn.

“A bird pooped on him,” Wooten said. “When that happens, that’s a sign of good luck.”

Oatman later learned that Ritchie (now Dick) Allen deferred his exemption due to an injury. That’s how Oatman became the first Black player to earn a full-season Tour exemption.

“I'm just glad I got the chance,” Oatman said at the time. “This is something I have always dreamed about. I feel like an NBA player who just got drafted."

Oatman seized the opportunity, leading all rookies in points, earnings and match play appearances and was second among rookies in average.

The southpaw came within one shot of a title, finishing as runner-up to Jason Couch at the 2007 Motel 6 Classic. Oatman needed two strikes in the 10th frame to surpass the Hall of Famer, but left a 10-pin on his second shot.

“He was just so deflated,” Wooten said. “He knew what that win would have done to not only him personally, but to the community, to the culture.”

As the lone Black player with an exemption, Oatman became a hero in the Black community.

“All of us lived vicariously through Billy,” Johnson said. “We were riding on his every shot. We felt empowered that we were being recognized by the fact that he was there and was competitive.”

When Oatman bowled on TV, Johnson said leagues back in Chicago would come to a halt. Everyone would run back and forth to the bar to see his next shot, Johnson said.

But along with that honor came an enormous burden.

“He was the Great Black Hope,” Wooten said. “He knew that every Black bowler in the country was going to be rooting for him. He had the charisma and all of that, but he was carrying the hopes and dreams of every little Black kid who ever wanted to bowl on his shoulders.

“He was up to the task.”

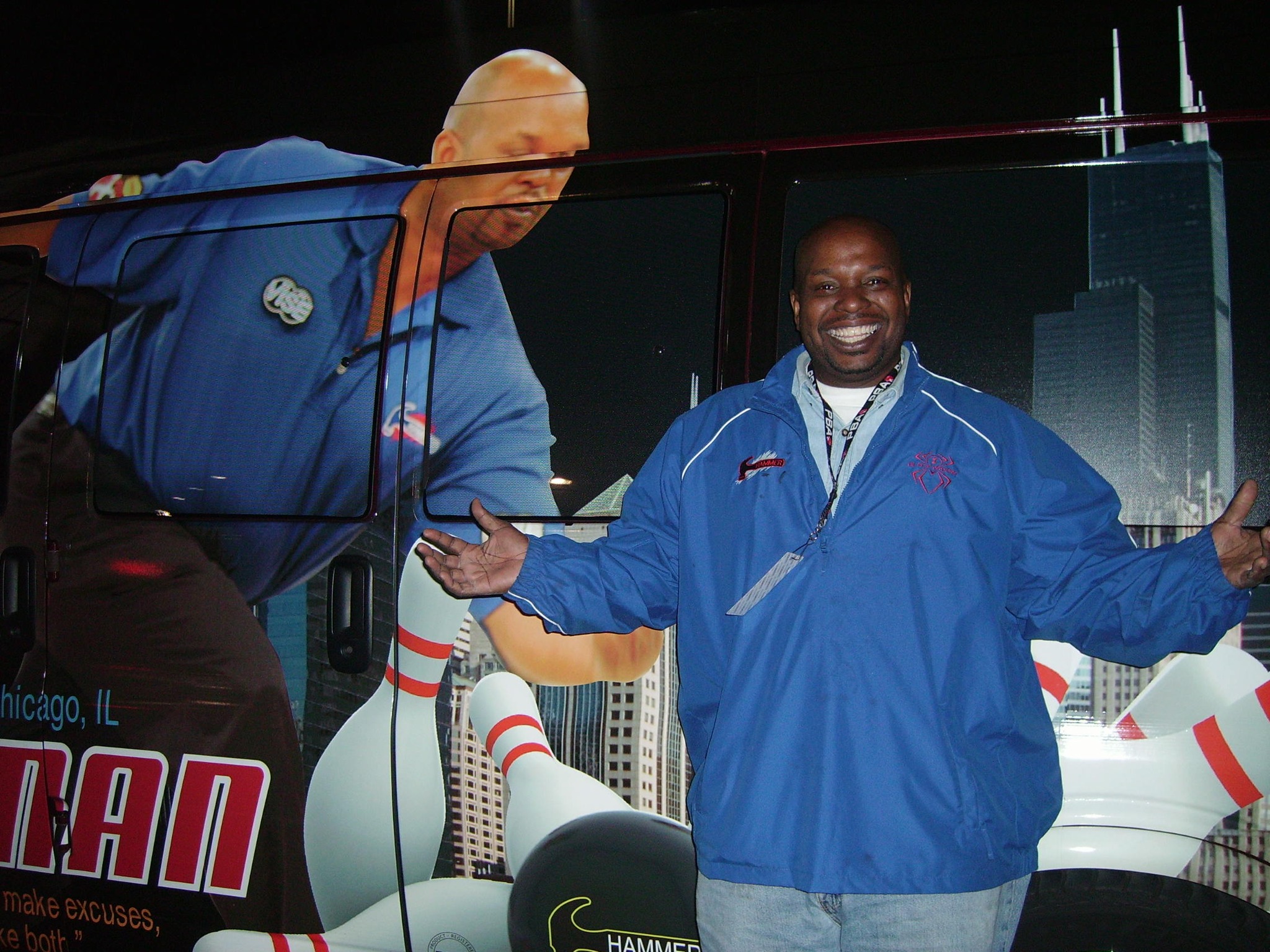

Oatman welcomed the publicity, driving all across the country in a decked-out van. The van featured a massive illustration of himself and his favorite quote: You can make money or you can make excuses, but you can’t do both.

Because of his iconic van, everyone knew when Billy Oatman was in town.

Even in what turned out to be his final weeks, Oatman continued doing what he loved.

“He loved people and he loved to bowl,” Annette said. “The last three games he bowled, which was three weeks ago, he won the jackpot in his men’s league in Chicago.”

Oatman’s legacy extends far beyond his Rookie of the Year award. He inspired a generation of Black bowlers not only to chase their dreams, but that it was never too late to do so.

PBA Jr. ambassador Jos Weems, a 13-year-old from Chicago, aspires to compete on the PBA Tour.

“I’ve been blessed to have met many bowling legends. Billy O was one of them,” Weems wrote on Facebook. “He invested time and words of wisdom in me. So much so that he asked for my autograph. He told Dad that he was passing the torch to me. He believed in me. He was a giant to many and because of his belief and investment in me, I carry him with me.”

George Branham III was the first Black player to win a PBA Tour title, capturing five titles between 1986 and 1996. In 2015, Gary Faulkner Jr. became the second with his Rolltech PBA World Championship title.

While Oatman, on paper, could not bridge the gap between Branham and Faulkner, Wooten said Oatman represented the PBA and opened doors.

“He did a lot for the culture. He did a lot for the game,” Wooten said. “For Black bowlers, that was our guy. He wore that with honor and pride.

“Quite frankly, he made us proud, man.”